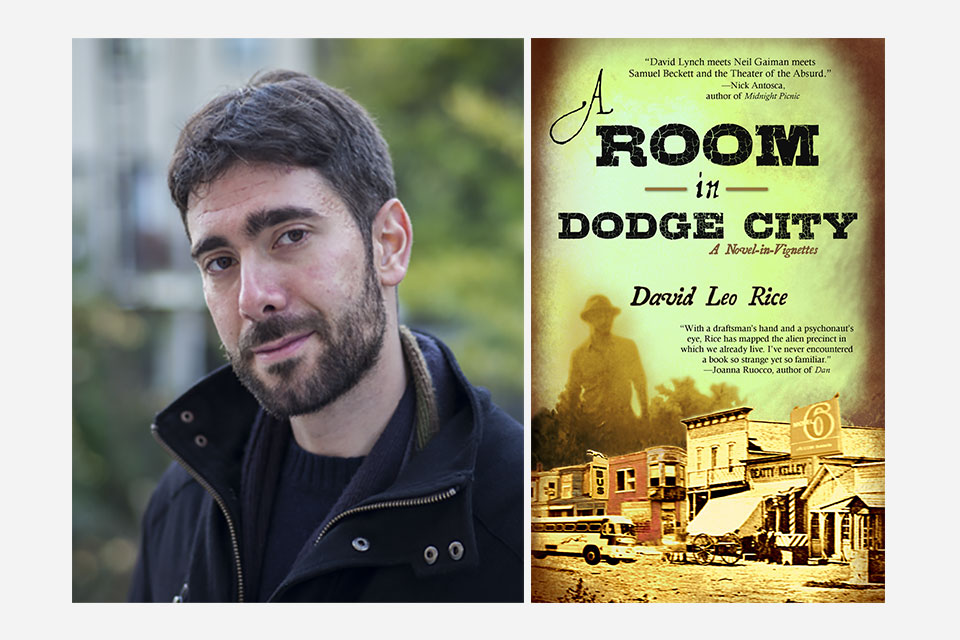

David Leo Rice’s first novel, A Room in Dodge City (2017 Alternating Current), won the Electric Book Award from Alternating Current. The novel has drawn a lot of comparisons to work by such artists as David Lynch, Neil Gaiman, and Edvard Munch among others. Told in linked vignettes, the cinematic work follows a drifter through a nightmarish version of the historic Dodge City. Rice, a writer and animator from Northampton, MA, now lives in NYC and earned a B.A. in Esoteric Studies from Harvard. His stories have appeared in Volume 1 Brooklyn, Black Clock, The Collagist, Birkensnake, Hobart, The Rumpus, The New Haven Review, Identity Theory, and Nat. Brut.

Thoughtful Dog caught up with Rice to talk about the relationship between prose and filmmaking and where he draws inspiration.

TD: I just finished A Room in Dodge City and it’s a wonderful, wild ride! The descriptions of the book are always a bit of a mashup: “David Lynch meets Neil Gaiman meets Samuel Beckett” or “If Edvard Munch knew alt-folk.” I think that is because the book is hard to describe in simple terms. It’s apocalyptic, dreamlike and post-modern like you’d expect from a Steve Erickson novel, but it could also be read as a version of hell like Sartre’s No Exit. Where did the idea for this novel come from?

DLR: I think the initial ideas for projects always consume themselves somewhere in the process of working on them, so that, by the end, it’s impossible to remember exactly how or why they began. The initial idea is like an enticing thread that I want to pull, but once I pull it and unravel whatever it was holding together, the thread has used up its purpose and is forgotten.

I was working on another novel, Angel House, which I found much more daunting and frustrating, so at some point I decided to also allow myself to write something freer and more fun, though in a similar world of a ritual-obsessed town—that was how Dodge City started, and then it took on a life of its own. I’ve found that if I can keep my initial excitement alive even as the work on a project goes on and on, my understanding of what I’m doing will change but my commitment to doing it won’t.

TD: The book is a novel in vignettes. Your main character is on a journey of sorts allowing him to be a voyeur to everyone and everything around him. This journey is presented in sharply drawn vignettes that are both darkly funny and grotesque. Your details really make the book jump—from the city of Motel 6s, the Unholy Family, hallways that turn into Southeast Asia, and The Bible Buffet—these sharply drawn details make it a cinematic book and I suspect that is why it has drawn comparisons to David Lynch. Why did you decide on the structure of a novel in vignettes? Any advice to writers on how to craft some of this amazing and precise imagery on the page?

I’m really glad you enjoyed the imagery and found the vignettes vivid—that’s great to hear! In terms of the original structure, at first I just wanted some freedom from the albatross of Angel House, which was this gigantic text file that I had no idea if anyone would ever see, so I decided to post sections of the other project online, piece by piece. The cardinal rule was that there could be no notes or other peripheral files—every thought about Dodge City, in its early stages, had to go into the draft itself. Over time, the vignettes started to suggest a more complex structure linking them all together, and I ended up writing a lot of new material once I’d put all the online vignettes into a single manuscript and considered them as a whole rather than a series.

As far as vividness and imagery goes, I tend to think that prose writers are, at heart, either poets or filmmakers. By this I mean that some writers start with words and phrases and build scenes from there, while others start with scenes and moods and then work to find the right words to conjure them. So, in terms of advice, I’d tell writers to ask themselves which one they are (or to reject the distinction if it doesn’t ring true to them) and then embrace that side of themselves, understanding both its strengths and its weaknesses. Either way, as you pointed out, specificity is key—the stranger the idea, the more clearly it should be presented.

I’m definitely in the filmmaker category. I feel a lot of tension between literature and film. Sometimes I feel they’re divergent media (and certainly very different industries) so that at some point I’ll have to make a lifelong choice between pursuing one or the other, but other times I feel an exciting cross-pollination, such that I’m often happiest when I’m writing prose while imagining that I’m directing a film, or animating while imagining that I’m writing a story, if that makes sense. The road not taken can inform the road you’re on, if you remain open to its appeal rather than growing bitter about not having taken it.

TD: This book won the Electric Book Award from Alternating Current. Can you tell me a little about how you got it published?

DLR: I just sent it to presses that I liked, and was thrilled when Alternating Current accepted it! It was great to win the Electric Book Award, but I don’t know how that process worked—this was all done through Alternating Current.

TD: You also worked with an illustrator, Christina Collins, for the book. You’re also an animator yourself, so were the illustrations something you knew you wanted for the book or did those come later in the publishing process?

DLR: I don’t know Christina personally, but I was very excited to learn she’d be illustrating the book, and very happy with the results—her illustrations are fantastic! For this book, the idea of adding images came later in the process, though I think about the graphic medium a lot, and have done a number of animations and recently finished a graphic novel with an illustrator friend. I didn’t grow up reading comics, but now I see graphic novels as the ideal marriage of film and literature—free and complex enough to allow the serious introspection and strangeness of literature without worrying about budget or actors, and vivid enough in their imagery to conjure feelings and situations that words alone cannot.

TD: A Room in Dodge City really draws on a lot of cultural references and is populated by dead thinkers like Harry Crews and Gottfried Benn as well as Mark Linkous. It seems like you must read voraciously. Do you read differently when you’re writing a book? Who are your biggest influences?

DLR: I love to read and I spend a lot of time doing so, though, like many writers, I wish I could spend even more. My to-read list is massive. I like that you picked up on how most of the real-world thinkers referenced here are dead—I conceived of Dodge City as a City of the Dead, a giant necropolis of discarded ideas and images that have been given a second life in the heart of the American continent. And I enjoyed the tension of putting real-life figures into such an otherworldly location—I found that imagining how these real people would behave in Dodge City was often more fun than making up totally fictional characters.

My favorite authors overall are Kafka, Beckett, Murakami, Kobo Abe, Marquez, Thomas Bernhard, Brian Evenson, Flannery O’Connor, Burroughs, Faulkner, Clarice Lispector, Pynchon, Ballard, Alan Moore and, as you mentioned above, Steve Erickson. I feel aesthetically aligned with the 20th century, much more so than any previous (and, perhaps, subsequent) time period.

For Dodge City specifically, the biggest influence was Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles—he was a Polish Jewish author and illustrator from the 1920s and 30s who wrote these extremely vivid, bizarre linked stories about life in his hometown on the Ukrainian border. He had a way of melding the drab realities of small-town life with something feverish, nightmarish, and even Biblical, which I tried to adapt to an American context here. There’s also a fantastic animation that the Quay Brothers made of The Street of Crocodiles, which expresses the beauty of the grotesque and the undead in a series of stop-motion tableaux.

In general, when I start a new project I think of a few books that feel relevant in terms of tone, setting, or theme, and I read them while I’m writing it, though I don’t tend to reference them explicitly. I definitely don’t subscribe to the idea that reading something too close to what you’re writing can contaminate it—I’ve found that more reading is always better.

A recent book signing in Northampton, MA, the inspiration for Dodge City.

TD: Even in your short fiction, you rarely go directly at a story in a traditional way. Does writing sci-fi, the grotesque or horror allow you to tackle themes differently?

DLR: I think of genres as boxes to draw from rather than boxes to fit myself into, meaning that I like to draw from horror or sci-fi or fantasy but don’t feel any particular allegiance to one genre over another. More than anything, I feel allegiance to a certain outsider point of view. The Drifter in Dodge City is on the outside of the town looking in at its strange rituals and situations with a combination of terror, disgust, and envy—I feel this way about art and literature.

In a larger sense, the idea of drawing from one box and using its contents to make something outside of that box is true about form as well. Writing a novel that’s informed by film, or drawing a graphic novel that’s informed by “serious” literature rather than comics, etc. . . . all of these cross-pollinations appeal to me, though I still believe that each form has its own rules.

Maybe this has to do with the effect the Internet is having on our brains: content is now so much more plentiful than context. Nothing we read or see stays in its own box anymore, but rather overlaps with and contradicts everything around it in a crazy snarl of information. If I think about the number of tabs I have open anytime I’m online, I really can’t say I’m reading any one page—I’m reading a strange composite of all of them. I think that literature should in some ways serve as an antidote to the Internet, but it also has to understand what the Internet is doing to us. 21st century literature can’t deny that we no longer see things in a linear fashion.

TD: You write quite a bit of short fiction and essays. What is your typical daily writing process? Do you have a favorite place to write?

DLR: I try to stick to a consistent daily schedule, though of course it often gets interrupted by “real life.” The hard thing is to preserve your conviction that writing is the priority and everything else, work-wise, should come second—it’s very easy to say, “oh, I’ll just take care of these little chores, then get down to writing”. . . and end up wasting the day. It’s much harder to do the writing first, even while knowing the chores are undone.

That said, I like to meditate a little after breakfast, then take my coffee into the back room of the apartment (I call it my “office,” though it’s more of a glorified closet), turn on Freedom (an app that blocks the Internet), and write until lunch. After lunch, assuming I don’t have to go anywhere that afternoon, I’ll read a bit, then do another writing session from 3:30 till 6:00 or so. I used to be a night owl, but lately I’m pretty much done after dinner. That’s the best time to read, see friends, or watch a movie.

TD: What’s next for you? You have a second book, Angel House. Can you tell us about it?

DLR: Angel House is out on submission now. We’ll see if it goes anywhere. It’s about a nine-year-old duo of aspiring filmmakers in a town that gets invaded by an evil presence called Professor Squimbop, who sails across an inland ocean in an ark called Angel House, which causes towns to sprout up wherever it docks. He creates one town per year, for the purpose of teaching the children there about death, and convincing them to sail away with him on his ark, like the Pied Piper. All the other children go, but the duo refuses because they believe they can achieve immortality through film. In a way, it’s a coming-of-age story.

Aside from this, I have my short stories gathered into a collection called Normal Stigmata, which is also out on submission, and I’m working on Dodge City: Volume 2. It focuses on Blut Branson, the Godlike (or Satanic) director at the heart of The Dodge City Film Industry, and the Drifter’s increasingly desperate attempts to either impress or overtake him. It’s a “kill the father” or “anxiety of influence” story, about power and the question of what happens in a small town when one person insists that their visions and dreams have primacy over everyone else’s. I’ve been reading and thinking a lot about dictators lately.

For more on David Leo Rice, visit raviddice.com and follow him on Twitter @raviddice.

David’s desk.

Howard Rice

1 May

Really enjoyed the book.

So well done in so many ways.

And liked interview as well.

Found it very enlightening.

For sure, will keep looking out for David’s future work.