Joe Clifford’s writing has been called “gritty,” as well as “taut, breathless, stark and powerful.” Of Clifford’s second book in the Jay Porter mystery series, December Boys (Oceanview 2016), writer Allan Leverone says “December Boys is more than great noir, or great crime fiction—its great fiction, period.” Clifford’s ability to look into the darkest areas of the human condition and from that, craft spare and compelling prose seems a hard-earned badge from a man who at one point in his life was a homeless junkie.

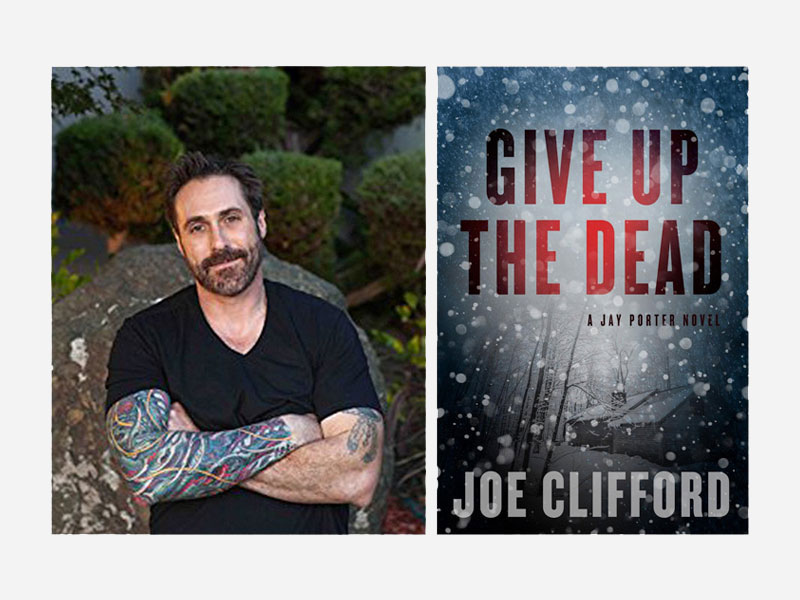

These days, Clifford wears many titles: Acquisitions Editor for Gutter Books and author of six novels including Junkie Love, Lamentation and the upcoming Give Up the Dead.

In the Thoughtful Dog Interview, Clifford talks about his new book, his process and surviving his past.

TD: In June, Give Up the Dead, the third in your five book Jay Porter mystery series comes out. Where did the idea come from? Did you always envision it as a series?

JC: The seed for the whole series was planted by my half-brother, Jay Streeter. I didn’t know Jay that well growing up, growing closer after my mom died. His life fascinated me. Like Jay Porter, my half-brother worked in the wilds of northern New Hampshire in estate clearing, which, as Jay Porter explains, is mostly clearing out antiques from dead people’s houses. Of course you have to notice the gold among the clutter. I loved that idea! In my novel, Jay is far more damaged. In real-life, my brother, Jay, is happily married with three great kids. But happy lives don’t make for great fiction.

Did I always see it as a series? Yes and no. I always shoot big, so I knew it was a possibility, but the reason the series has been sustained for so long (in addition to people buying my books!) is owed to my subconscious, which created far more threads than I was (consciously) aware of. The world of Lamentation (the name of the first in the series, based on the mountain range that encloses my fictional town) took on a life of its own.

TD: You’ve mentioned that you write the Jay Porter series pretty easily (a month for a first draft) but that some of the other fiction you’ve done has taken much longer? Can you talk a little about that? What is your writing process? Is it the same for each book?

JC: First I should clarify. When I say first draft in a month, I mean a shitty, shitty first draft (to borrow from Anne Lamott). People who die on page 10 are alive on page 80, etc. There is a lot to clean up. But, yes, I can generally get a basic plot, an arc, a beginning, middle, and end very quickly in the Jay Porter books. That is mostly because I know the character and world so well, and to a degree, there is a formula. I know people bristle at that word. So we can use template if you want. I personally love formula. All writing is a formula. Lee Child, James Paterson, Dennis Lehane, writers I admire, work within the same confines. When one says “formulaic” and/or “contrived,” what they mean is the writer did a bad job; you can see the strings behind the curtain. But all art is contrived by definition.

The other books take longer because I am creating new worlds and characters from scratch. I have to learn who these people are, understand why they are where they are, or the work lacks authenticity (or to sneak in my favorite ten-cent grad school word “verisimilitude”).

TD: Let’s talk about your journey. Your first novel, the autobiographical Junkie Love, chronicles your struggles with addiction. You grew up in Connecticut, quit Central Connecticut State University and moved to San Francisco, but within a year, you were hooked on meth and heroin. From there, you went to L.A., where you became homeless. I think I read somewhere that you had been in something like seventeen rehabs. In 2006, you had a near fatal motorcycle accident and broke your back, pelvis and punctured a lung. How did you get from there to where you are now—a man with a successful writing career a wife and child, and an M.F.A.? Was writing part of your recovery process?

JC: You summarized that so well, there’s no reason to read the book! The answer to that one is probably too long to cover here. Junkie Love answers a lot of those questions, though since the “story” in that one stops in 2004, there is nothing about life afterwards, which, as you hint, included some eventful stuff, too. The motorcycle accident, a divorce, the harrowing experience of grad school workshops. I’m not sure which of those was worse. I’m kidding. (It was grad school workshops.)

Was writing part of the recovery process? I hate to hedge bets again, but … yes and no. I mean, writing is therapeutic, but I am wary of using that term as it relates to professional writing. There is the kind of writing one does to get all their emotions and feelings out. That’s journaling. Nothing wrong with it. I’ve done it. But once you start writing for a career, you no longer get to “write just for me.” You have an audience you have to consider. You have agents, publishers, editors. It is a job. And I say this because I want to help others get published, and the single biggest handicap I’ve seen writers give themselves is this belief that they write for themselves and no one else. I even read bestselling authors saying this. But it isn’t true. For anyone. Of course you must be true to your own voice; you have to be authentic. I’m not advocating some kind of focus tested, middle-of-the-road pap. If you are edgy, be fucking edgy. But I believe it is essential to understanding that writing (professionally) is more than just throwing out words about how you feel. It is a talent, but above all writing professionally must be treated like any profession: with respect and dedication, if one hopes to succeed. (Sorry for the preaching. I’m answering this on Sunday, and like many writers I am a lapsed Catholic. Oh, the guilt.)

TD: Writing isn’t the easiest thing to do, but you’ve said it is a lifestyle choice and how you see the world. Can you talk a little about how writers see the world differently?

JC: I think one needs to be a bit mad to write. That sounds like something Pink Floyd said in an interview, either Waters or Barrett. I think writing, the skill, can be taught. Meaning, anyone can learn to write well enough to be competent. But the natural born writer? You just know that shit, and usually from early on. You’re the weirdo scrawling stories in the notebooks in the 5th grade; creating elaborate scenarios for your action figures and dolls; it’s a lifestyle. But I don’t think it’s necessarily a choice. If I said that (lifestyle choice), I probably meant it in terms of once you decide to become a professional writer. But I think true writers/artists are born that way. You may or may not pursue that to an end. But, yeah, you see things differently. You see the old man eating onion soup in a 24-hour dinette alone and it hits us differently. We use these personal stories to communicate with the world at large, and, one hopes, shine a little light on this human condition.

TD: There’s a great quote from you about agents. You’ve said, “[Agents] read to say ‘no’… And if you think getting an agent is hard, just wait till you have to entice a publisher.” How did you find your agent, Elizabeth Kracht? After you found Elizabeth, the process started all over again finding a publisher. Was that process smooth?

JC: Another great question. With a long, long answer. In short, yes, agents (and editors and publishers) read to say no out of necessity; they have so much shit to read and get through. This isn’t to say these people don’t love literature—that is why they are in their chosen fields. What I mean is, because of the sheer volume of material they have to read, the agent/editor/publisher doesn’t have a lot of time, and he/she will be quick to say no. A lot of times, we have books that we ourselves, early on, at least, think, “I know it’s slow starting, but all this pays off, trust me.” You may be right. But you don’t get the time for the pay off. Unless you hook them right away, chances are they won’t be around to see your brilliant finale. You, the writer, must not give them a chance to say no; you get them in your clutches right away, and don’t let go.

Here is the answer to the second part of that question, and one that will depress the shit out of most. No, it wasn’t smooth. It almost never is. And worse? There is no endgame. You think, “If I can just get an agent…” Or “If I can just get a book published…” But it never stops. There’s edits and the next book and sales and marketing, and if you book doesn’t sell, you don’t get that second book. My point: writing is like a rainbow: there is no end. It’s a fucking illusion. The satisfaction we seek, corny as it sounds, must come from within. And I’m not going to leave anyone here with the impression I am healthy, whole, happy. I’m still the same fucked-up mess. No, I don’t shoot heroin anymore. But like most writers, I need a lot of validation. The joke I often use to define this is: we, as writers, are collectively in more dire need of a hug than any other faction of society; and we’ve entered a field defined entirely by degrees of rejection.

My specific publishing journey is like 99.9% of any published writer. A crooked path, filled with lots of tears, and the victories are never as sweet as the defeats, which are crushing. Yet, I wouldn’t have it any other way. Maybe that’s because, like most writers, I am full of self-loathing. More likely, though, I think it’s just because this is the reality of writing, and I love being a writer, love the work, and, yes, even the headaches and heartbreaks. I am a writer. It is who I am. It is what I do.

TD: You run a reading series in the San Francisco Bay Area called Lip Service West. What is the concept?

JC: The concept is true stories, 1,500 words, first-person narratives. Most of our stories focus on the darker side of life. The series is currently on hiatus, just because of deadlines and other life stuffs. I’m sure we’ll pick it back up at some point.

TD: You’ve said that there is a feel to novel writing, an inner peace, where you and the text become one, and you know where to go and what to do. Can you elaborate on that a little?

JC: Since I feel like I’ve been a little more didactic in this interview than I’d like, let me close with an anecdote about writing Jay Porter that I think will illustrate what I mean. Jay Porter has an anxiety condition, as do I. But when I write the Jay Porter novels, and only when I am writing them, I develop a left eye tic. My eye literally twitches when I write these books. The more harrowing Jay’s experiences become, the worse the tic. But it’s not just that. My favorite example of this phenomenon is that I wrote a scene two years ago in which Jay suffers a near-catastrophic vascular injury to his saphenous vein, almost losing his leg. I know nothing about human biology. I picked the name of that vein because it sounded cool. Two weeks ago I had to undergo surgery because a vein in my leg was back-flowing to my heart (a result of the motorcycle accident). The vein that had to be cauterized? The saphenous. I didn’t know I had Jay’s problem until a few months ago, and certainly not when I was writing that scene. So art imitates life, etc.? Maybe, on some level, my subconscious knew there was a problem. Maybe the problem manifested because I am so ingrained in the character. Probably the former. But I think the latter makes a better story.

JUNE LORRAINE ROBERTS

27 February

Joe is an incredibly talented writer and I’m sending him a big karmic hug.