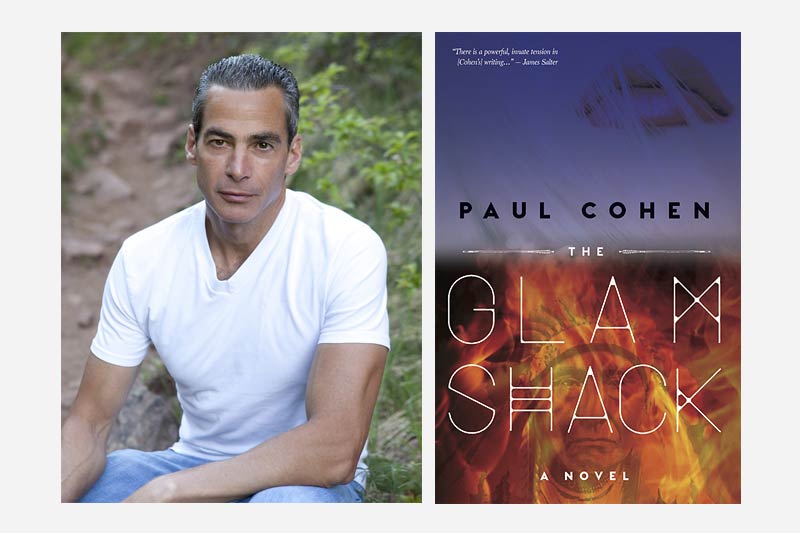

The late writer James Salter, described Paul’s Cohen’s work by saying, “There is a powerful, innate tension in his writing which comes not only from his voice but from his particular way of looking at things, an unusual way, and in art in fiction the only real worlds are likely to be the unusual.” In Cohen’s debut novel, The Glamshack (released June 15, 2017 by 7.13 Books), this voice Salter describes is fully showcased. Described as an “exceptionally rare, uncategorizable novel” by Josh Kendall then Executive Editor at Little Brown when he nominated it for a Pushcart Press Editor’s Book Award, The Glamshack has also been included in the “Most Anticipated Small Press Books of 2017” list from John Madera at Big Other. Cohen’s short fiction has been published in Tin House, Five Chapters, Hypertext and Eleven Eleven, and his nonfiction in the New York Times Magazine, Village Voice, Details, and the Christian Science Monitor. Thoughtful Dog caught up with Cohen to talk about his new book, his process and the interesting road to publication.

TD: In your new book, The Glamshack, the protagonist Henry Folsom has just 12 days to change the mind of his love, a woman you just call Her. After that, She will leave her graduate program to return to her fiancé in New Orleans and Henry will lose Her forever. This novel such a close-in depiction of a love that its almost claustrophobic (and I mean that in a good way). You’ve captured that obsessive desire that is present in doomed love. The book has a great, stream of consciousness that is almost Proustian. Where did the idea for this book come from?

PC: That is a beautiful description of The Glamshack and a totally fair question and I wish I had an answer like, I thought it would be illuminating to insert a man into the stereotypical, inferior position of “other woman” and through telling his story carve a glowing new cave into the obsidian of the human heart, or, I saw leaves floating on the steely surface of a swimming pool and I thought God, that is the loneliest image I’ve ever seen, and The Glamshack just flowed from there. The truth is the idea for The Glamshack came to me the old fashioned way—from heartbreak. I wrote the first draft in a fever in a borrowed pool house in the woods during an El Nino winter, when the rain came down hard and ceaseless and cold, drenching the wood I’d cut for the stove, and coyotes clicked their canines outside my window at night. I wrote because it made me feel better. I wrote what I knew, as they say, until I had a platform solid enough to climb atop, at which point I began to craft the novel.

TD: Talk a little about the process it took to create it. It’s a poetic book with rich language that I know takes work. How did this story evolve through the editing process?

PC: As a kid I rode retired racehorses bareback on my friend’s farm through dark gnarled forest and blurred cornfields, full speed and out of control, face pressed to musty mane, cursing the malicious beast while praising its beauty with howls and snorts. Writing The Glamshack’s first draft went something like that. When the draft was done, I believed I felt its slick, quivering power. I showed it to my first reader and he agreed I had a hold of something. He also had a hell of a time just following the story one page to the next. So began the iterations, which I liken to a series of translations. Horse to Greek, Greek to Latin, etc. I axed the naysaying talking fish when I finally heard it for what it was—cute. Ditto for the occasional second person narration. I worked hard at the convoluted timeline so the reader wouldn’t fall through chronological cracks. I crammed a clever plot twist into the ending until I realized all it accomplished was to flatten the character of Her, at which point I took it out. When my editor suggested losing the airplane bar—the setting for 3 of my dearest chapters—I was incensed. Hands off the goddamn bar! And then I did it, I lost the bar, and he was right, the book was better. The trick of revision, I think, is to exert control without dimming the dangerous beauty of your slick, quivering beast.

TD: I love that you refer to Henry’s love only as Her or She. It puts a bit of distance between the reader and Henry’s love. It was such an interesting choice (and works so well) that I have to ask why you decided to do that?

PC: I love this question because it made me realize something for the first time: I never considered giving Her a name. Which strikes me as strange. The natural thing would have been to give Her a name. Names particularize objects, especially objects of affection. At least I might have fished around for a name until realizing nothing fit. Instead, right out of the gate (what’s with the horse metaphors?) I named her Her. Why? Because a central problem in the book deals with the chasm between Henry’s vision of Her and the actuality. The need to close that chasm helps drive the narrative. Henry’s vision of Her is one of incandescent beauty and noble presence; his goal is to see Her as disfigured and ordinary. Which is to say, his goal is to find incandescence in, and beyond, himself. Fortunately (and maddeningly), for Henry and Her, She is neither incandescent nor ordinary. And She is both. Which is to say, She is everything.

TD: Your road to publishing this book has been interesting. The Glamshack was nominated for a Pushcart Press Editor’s Book Award by Josh Kendall, who was then a senior editor at Viking, The Editor’s Book Award is given to a favorite manuscript that an editor has tried and failed to acquire. Ultimately, this book did see publication with a small press, 7.13, and will be released as their debut title on June 15th. Can you just walk me through the process of trying publish this book, first, to a Big Five publisher and then to a new small press with a very interesting mission?

PC: I sent an earlier incarnation of the book to James Salter, who was a teacher of mine at Iowa and with whom I kept in touch long after graduating, asking him for an agent referral. Salter never said a word about my ask (“The emissary does not stoop to banter”) but couple of months later I got a call from an agent in New York who said she’d received the manuscript from Salter and had just finished reading and was “breathless.” At that point I figured all the elements had fallen into place and now I stood on the cusp of worldly recognition and fortune in the form of those cushy visiting writer gigs. Alas (and in retrospect, thank God!), this didn’t happen. I received glowing rejections from editors and in some cases apologies that they’d tried to acquire the novel but had been shot down by higher ups. Josh was in this latter group. He was passionate about the book because, as he wrote in his letter nominating it for the Pushcart, it was “that rare, uncategorizable novel that serves as a reminder of how commonly un-daring contemporary fiction is in general.” No one won the Pushcart that year, and I put the manuscript in a drawer and embarked on another novel. Then Leland Cheuk, who’d read an earlier version of The Glamshack, founded 7.13 Books in Brooklyn with the mission of publishing the best—and in some cases the best overlooked—literary debuts. He asked me to be his debut debut. He had brilliant ideas on weaponizing The Glamshack. He’s a gifted editor and a man of great integrity, and I was honored to accept.

TD: The protagonist, Henry, feels he needs to take a stand against the the Fiancé. There is a war going on with a fiancé in New Orleans and a battle for Her. Can you talk about you use of the 19th century Sioux wars as lens for this love story?

PC: At some point while writing that demon-driven first draft, Henry’s challenge shifted from how to endure the burn of Her absence to how to see his struggle for Her in terms greater than either of them. Heroic terms. No matter the outcome. Otherwise, he reasoned, what was the point in soldiering on? Either we humans are composed of God particles, as the physicists say, or madness particles, as Henry fears. At the time I was reading William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice and Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Star, a nonfiction book about Custer and Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse’s struggle was, to me, the essence of heroism. He fought for a gorgeous liberty. That the outcome was tragic, and that Crazy Horse probably had an inkling of this all along, only elevated his stature. Then I had an idea that felt, well, criminal: what if Henry used Crazy Horse’s struggle as a lens through which to view his own war? Might that reveal in this tale of bloodied love the presence of the heroic? After all, wasn’t love, like liberty, one of life’s great essentials? The idea seemed scary, and a little sacrilegious, but I took heart in the way Styron integrated historical scenes from the Holocaust into his sordid love story, and I set about turning my twisted tale into classical tragedy.

TD: What is your process?

PC: I can revise anytime but only in the morning do I have the strength to face the terror of the blank page, and even then I’ve got to get up at least an hour before show time to (figuratively speaking of course) shadowbox, which includes coffee. Salter once told me don’t read before you sit down to write, and I must have taken that to heart because I never do. Once seated, I re-read my work from the day before. Or I play around with sentences. While this helps put me in the right place I have to be careful not to get snagged by editing or re-reading. If the writing isn’t happening, I tell myself to do it badly, as badly as possible, almost like a game. If it is happening, I’ll work for hours without stopping. This includes pacing, which helps me untie narrative knots. That said, I’ve never found thinking about the work particularly fruitful; the bulk of my progress occurs in the act of writing, with only a broad notion of where I’m going—the proverbial headlights in the fog. My favorite place to work is in my house alone. I like the feeling of uncluttered space around me, which is why I’m not comfortable in coffee shops. For me, nothing caps a good writing session like running trails on the mountain behind my house. Followed, when possible, by happy hour.

TD: Who (or what) are your inspirations?

PC: As a writer, I quicken to the music of the sentence as well as to a bold vision of the mystery I sense comprises our core. Saul Bellow has both and his novel, Henderson the Rain King, first inspired me to write. Cormac McCarthy is another inspiration. His novel, Blood Meridian, might be the most beautiful book I’ve ever read. And the truest, for at the same time the book’s content protests (too much, I doth think) the existence of mystery, the voice thunders down from the mountain with biblical force. I love the work of Flannery O’Connor and Faulkner and Louise Erdrich and Laird Hunt. And James Salter, not only for personally helping me to stay the course as a writer, but also for his singular ability to mine the luminous in a seemingly ordinary phrase. From Marilynne Robinson, another teacher of mine at Iowa, I received a gift critical to any emerging writer: the conviction to trust in my own, strange, vision. Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, while not fiction, both thrills me on a philosophical level and grounds my work. Bible stories serve a similar function. And of course Crazy Horse and his compatriots and their devastating, glorious story that is not ended still.

TD: What is next for you? Your next novel, The Sleeping Indian, was just named a finalist for the 2016 Big Moose Prize from Black Lawrence Press. What is that book about?

PC: The Sleeping Indian is a different beast. While it does have a love story, that’s not the focus. The narrative cuts between the woods of Wyoming, where the main character lives outside with a few other climbing rats, and an expat community in Paris, where, years later, during a spate of terrorist bombings, the same character has gone to hide. Not too far into the book we learn from whom he’s hiding, and later the story reveals from what. I want the reading experience to be physical and suspenseful and eerie. Right now I’m focusing on tying the final, critical knots of plot, which for me is hard work. What I want from this book is a creature strange, rich and taut, one that darkly delights.

TD: The early reviews for The Glamshack have been great! You really persevered with this book and that has to feel great. Any advice for other novelists struggling for their work to be published?

PC: I think the most important thing I learned is that writing is not an avocation or even a vocation—it’s an identity. A writer is a renegade; we don’t follow instructions well because we’re busy searching for new suns. This proud notion freed me to do the silly things we all have to do to put food on the table with less shame, reminded me of the need to write regularly in order to stay true, and counseled me to play the long game. That said, every writer, no matter how confident or proud, needs a reassuring nod now and then from the world. Keep sending stories to journals. Connect with other writers. Go to conferences. Read. Reach out to established writers without asking for permission. Stay the course.

COMMENTS ARE OFF THIS POST